Hello, welcome come aboard. This post is the longest I’ve written. I had a lot to say and while I have tried to keep my thoughts brief, WordPress tells me you’ll need a cuppa and snack or given this is not my usual light reading perhaps a nice single malt whiskey. If you’re only interested in pretty pictures of ruins, I suggest you stop reading at the *. If you would like to know why the ruins exist, read on however I warn you there’s politics, war and even a little literary license (not mine for a change)

Recently we had the opportunity to revisit the lovely town of Fethiye. During our last visit we explored the Old Town and had fun playing “Indiana Jones” at the Lycian rock tombs. This time we decided to visit a very special place nearby that I had heard about from some friends. I’m usually the first to line up for any historical site. I love ruins. I love museums. I revel in tales of old and these places are remnants of stories. Stories of people’s lives, their hopes, their loves, their chores, and hardships. However, this town, now known as Kayaköy, is a sad place. Its ancient history is overshadowed by great hardship and tragedy in more modern times.

Kayaköy was once known as Carmylessus. It’s just 8 short km over rugged hills from Fethiye and about the same distance again to Gemlier Adsi (St Nick’s Island) on the coast. The region was inhabited for centuries, reaching the lofty heights as a Christian bishopric during the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (640 CE). There’s evidence to show the St Nick Island inhabitants (Christian monks) would flee to Lebessos in time of pirate attacks. The town thrived well into the 20th century, however it is now a ghost town.

When I mentioned to Ian that I wanted to visit Kayaköy by bus he was ambivalent, that is, until I explained it was a “modern” ghost town. Intrigued he agreed and we set out on a bus that reminded me of an All-American yellow school bus, only white and a third the size. Unfortunately, in an effort to accommodate as many people as possible legroom was non-existent. Our cunning plan to be the cool kids at the back of the bus was soon foiled as we were forced into a corner seat. With my knees around my ears, I looked at Ian laughing at me and asked, “if he was mocking me for my choice of bus.” Thankfully the trip wasn’t too long and we were treated to a view of the suburbia behind Fethiye and the forested hills along the way.

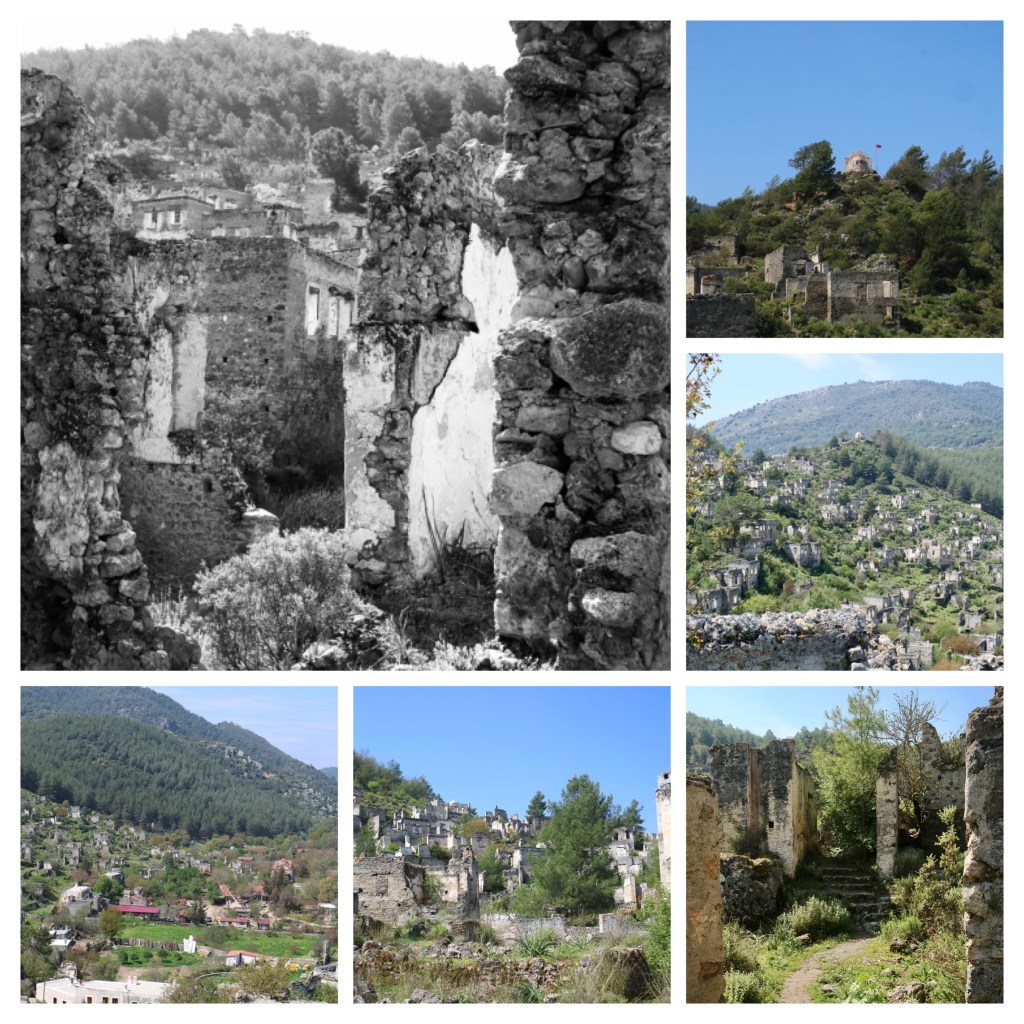

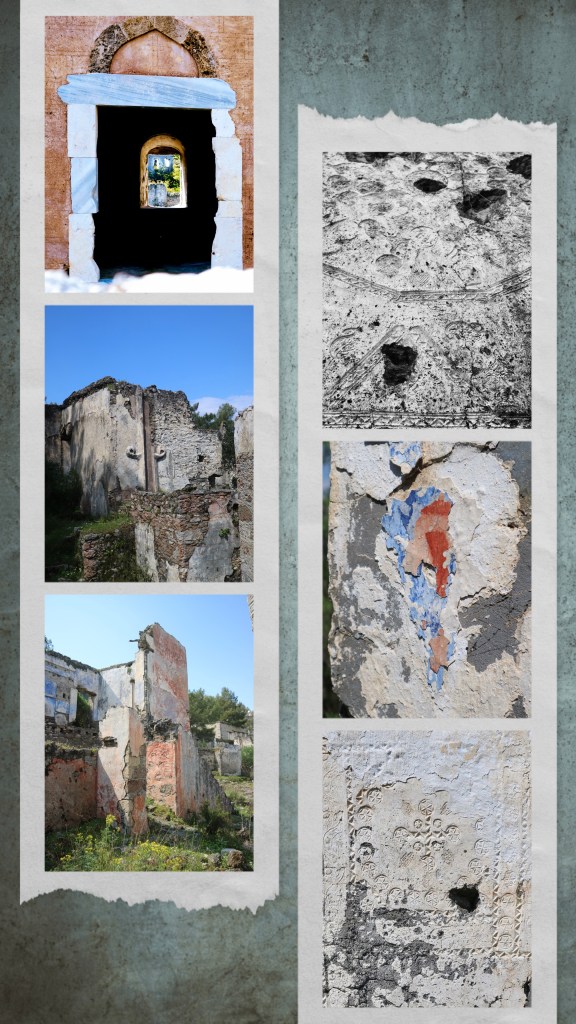

On our arrival we discovered Kayaköy that was once home to around 10,000 people is/was a town of contrasts. To the left of the main road there’s a craggy hillside. The ruins of two and three storey stone houses and buildings cling to the slope. The houses, and their underground cisterns, are all open to the elements. Nestled among the houses there are two schools, a municipality building, fourteen chapels and two churches. The most prominent chapel sits at the apex of the hill. It’s single room is tiny, room for perhaps six people, it has two postcard windows. One open seaward, the other behind the alter overlooking the town. The churches are bigger and grander, the other chapels would be difficult to recognise if not for the signs. At one time there would have been an ossuary behind the largest of the churches. These too are reminiscent of much old ruins; no doors or windows remain, roofs gone and walls tumbling down. Trees and shrubs reclaiming the environment. The town also suffered greatly when an earthquake shook the area in 1957.

The thoroughfares through the town are stoney tracks and stepped paths. There’s only room for man and beast, no space for wagons or cars.

Even in Spring the hillside reminds me of the Australian outback, shades of muted greens and brown, with only scraps of the colour and vibrancy I’ve come to expect from a Turkish Spring. Nature is winning. (funny thing, when I returned to select photos for this blog, I discovered that the township was a riot of Spring colour and not nearly as muted as I remember. I think my great sadness for this town overshadowed the vibrancy of memories).

Below the hillside, the valley is green and lush. The soil is rich and consequently much is given over to farming. There are wooden and brick houses there too. Though these show signs of inhabitants, atelliste dishes, washing airing in the breeze, the enviable cats and dogs. These homes skirt the flat land so there is no boundary between the town on the hill and the farms except the restaurants and tourist stalls along the main road. Here we found the first of the mosques sitting squat and imposing.

*Until recently (early 1900s) the hillside was populated mostly by Greek Christians and the valley by Turkish Muslims. There was also a thriving though small Armenian quarter. The Greeks, on their hill, were largely “middle class”, shop owners, government official, artisans, and the like. Their children attend the Greek school, learning to read and write, mathematics and science. The Turks, in the valley, were farmers, though there would have been a Turkish landowner, much like an Englishman nobleman who owned all the land. Their kids went to the mosques for their learnings. It’s unlikely they would have learned the three “r’s” instead focussing on the learning the Koran and teachings of Mohamed.

There were certainly similarities and crossovers. The religious men of both denominations would have been influential, the women probably more so in the day to day lives of the town. Turkish was spoken but written using the Greek alphabet.

A very heavily romanticised version of this village life was written by Louis de Bernières, of”Captain Corelli’s Mandolin” fame, called “Birds without Wings” (April 2004). This is a story of a town called Eskibahçe, which the author acknowledges is based on Kayaköy (and other towns that suffered the same fate), and tells of the last few years of the town as a focal point for the broader historical event that began with the decline of the Ottoman Empire in the late 18ᵗʰ Century and ended with the birth of modern Türkiye in 1923.

This is not a happy time in the world generally and in this region particularly. Within the Ottoman Empire, factions pushed for modernisation and the abolition of the Sultanate in favour of a democratic nation. During this turmoil, World War I breaks out, and the Ottomans ally themselves to the Germans. Most of us know of the Allied campaign at Cannakale (Gallipoli). The book gives an admirable account of this battle/s from the point of view of the Turks. De Bernières is graphic is his description of the appalling conditions that the soldiers, Allied and Turks alike, faced. While the war rages on, elements of Ottoman government attempt to further the Republican agenda. After the war much of Ottoman Empire was partitioned and so began the British, Italian and French occupation (1918-1922). This period overlapped the Turkish War of Independence (1917-1923). The Armitistice of Mindanya signed an 11 October 1922 and the Treaty of Lausanne signed on 24 July 1923 officially settled these conflicts. As part of the settlement negotiations, Greece and the newly formed Grand National Assembly of Turkey lead by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk) agreed to an amnesty for war crimes committed and made arrangements for the exchange of citizens that happened to live on the wrong side of the border.

Throughout this period of unrest, the Turks committed atrocities against the Greeks, Armenians, Syrian and Allied prisoners of war. The Greeks were given the opportunity to leave Turkey, voluntarily. Those that refused to leave willingly where forcibly removed through death marches; being permitted to take only those possessions they could carry and these were often “confiscated” by the soldiers. Those that still resisted were put to death. The Greeks reciprocated against the Turks and had a good go at the Armenians, as well. When researching I found plenty on the Greek and Armenian Genocide committed by the Turks. These, and the book, describe unspeakable cruelty and wanton bloodshed. Notably, I could find little on the atrocities the Greek inflicted on the Turkish people at this time. The one solid fact that everyone agrees on is that the victims were mostly innocent women and children left behind when the men went out to fight for their cause.

The triple contagions of nationalism, utopianism and religious absolutism effervesce together into an acid that corrodes the moral metal of a race, and it shamelessly and even proudly performs deeds that it would deem vile if they were done by any other.

Louis de Bernières, Birds with Wings, p324 (eBook version), April 2004

So, it is easy to believe that Kayaköy and others like must have been strife with unrest, civil disobedience and hate crime. Yet the book, which is based on oral accounts of those that lived in the region at the time or grew up with the stories of their elders, tells a different story. Eskibahçe was peaceful, there was no overt segregation (though the Armenians were generally disliked), except in religion. The women folk were friends, the kids played together, and the men played backgammon in the town square. There is a thread throughout the book regarding the gendarme’s prowess at the game, having all the time in the world to build their skills. There are snide comments behind closed doors and few good-natured snips, much along the lines as you would hear from rival football team fanatics among the town folk. Yet, the Muslim women are not above asking their Christian friends to leave offerings to the Virgin Mary Panagia Glykophilousa. The Imam gives a blessing to a Christian baby. The Christian men seek advice from the Imam. Even the Greek schoolteacher who is overtly pro-Greek is for the most part humoured. The town folk share a mutual undertone of rural mysticism and folklore.

When the soldiers finally come to take the Greeks away, the Eskibahçe, the Turks provide aid to their neighbour, they agree to care for their homes and belongings and some Turks make the journey to the port to ensure their friends are not hurt along the way. The book briefly tells of the arrival of the Greek Muslims and the distress of everyone involved in the exchange process, this is soothed eventually as acceptance of the people overshadows the method of their arrival. As the resettled people were unable to take their wealth with them many lived out the rest of their lives in poverty or near poverty. Most of Greek Muslim were farmers, like their Turkish counterparts. The lose of much of the Greek middle class in rural areas has held Turkey back. The Christian Turks were ridiculed and shunned in Greece. Many would have found it difficult regrow their prosperous businesses in their new homes.

Finding Turkish historical records and accounts of rural life (and the genocides that occurred) was hard. This is why I relied so heavily on Birds Without Wings. I’ve read a couple of reasons for this lack of written history, all are to have contributed. The Ottoman Empire was largely Muslim and did not believe written records of daily life were meaningful and importantly this is the period in which Mustafa Kemal Atatürk rose to power. He is revered here in Turkey as a modern man, great military leader and a benevolent leader. Atatürk literally means Father of Turks. He strongly believed government should be non-secular, democratic and looking towards the future not the past. Here the focus on Atatürk’s advancements: he was pro-suffrage, believed in non-secular education for all (including women) and wanted his country to be an active participant on the world stage. He also banned the fez and turban, making it mandatory for all men to wear western style hats in public places. This is known as the Hat Revolution. The Turks have written their own history, after all they were the victors.

I didn’t read Birds Without Wings, until after our visit to Kayaköy. I knew some of the modern history of Turkey and its impact on villages such as this one. And to say that I was ambivalent, bordering on reluctant to walk the streets of this ghost town, would be an understatement. This may seem contrary, but my love of history is largely restricted to ancient history. To times and places where I can tread without fear of seeing the futility of our modern world or find yet more evidence of our persistence in acting on our differences rather than embracing our sameness. However, having been in Turkey for eight months, I wanted to further understand this wonderful country. To do that, I need to know this awful history, so I can understand the people I meet. Frankly, as a result of this excursion into modern history, I’m even more surprised at how welcoming the Turks are given that just over 100 or so years ago, Australians were part of an invading force that attempted to tell them how their country should be run. At least that is how it must have surely seemed to the grandparents of the elderly folk that we pass every day on the streets and laneways here in Turkey.

I promise I will return to lighter and more ancient topics in coming posts. In the meantime, fair winds and an dearth of sea monsters for you and your loved ones.

Great post Betty, my ignorance of all this is something Mandy tries to amend subtly with book suggestions. But when I have your blog it is much more simple to gain knowledge 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Mick! I’ve been trying to get Ian to read this book too but I don’t think he believes me that it’s not soppy love story.

LikeLike