Hello, welcome, come aboard. We hope life has been kind to you in the last little while. It’s hard to believe that it’s the end of June! The year is half gone already. I was thinking about what we’ve done this month and had to chuckled. Didn’t I say something about “going slow”? It’s not been a full month since we last posted to the blog. In that time, we’ve left Türkiye, entered Greece, visited many anchorages/towns most of these on Greeks islands, travelling over 200 nm (370 km) including one 12-hour moonlit trip. That distance travelled doesn’t include the road trips we’ve also done to explore a few of the larger islands. We’ve even had our mate, Lesley visit with us for a few wonderful sun-drenched days. We’ve also been visited a couple of times by Meltemi winds (strong Northly winds) which have kept us in port or on the boat for days at a time.

This all seems crazily busy, and yet it still felt like a “go slow”. Some places we stayed for days, others we stopped in over night and kept on moving. I haven’t felt rushed except to say we were keen to move past the Meltemi zone (aka the Aegean Sea). Not just because of the Meltemi winds but because of the madness that is the summer charter boat season. There are about a dozen islands that we’ve not explored including some pretty famous ones, like Santorini and Mytilene. Thankfully, we will be returning early next year (outside the Meltemi and charter boat season) to explore these islands at our leisure. We figure this is advisable as, ironically, the winds make me cranky, and the levels of ineptitude and dangerous sailing we often see among the chartered boat crews is enough to make even my peaceable captain want to raise the skull and cross bones.

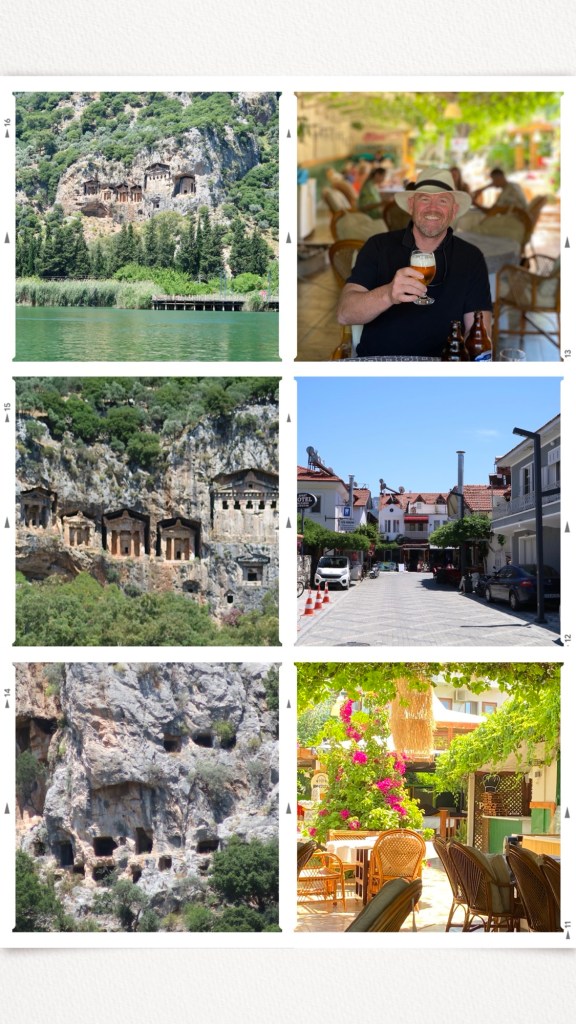

Selimiye – “the French Riveria” of Türkiye?

Anyway, when we left the last post, we were leaving Bozburun to stop off in Selimiye (both in Türkiye) as we were keen to share this pretty region with SV Chill. One very enthusiastic shopkeeper told Ali and I that Selimiye is known as the “French Riveria” of the Turkish Coast. However, we decided this was more a justification for the $600 price tag on the bag I had been eyeing off than any reality. Selimiye is a pretty, little village with a few lovely shops and bars along the shore and not much else. However, it’s worth visiting just for the amazing fjords-esque entrance to the bay. On our sail in this time, the weather was so lovely that Ian and I wove between the islands doing two knots (less than 4 km) under sail while we enjoyed our lunch. There are ruins on the islands and the sounds of goats in the distance.

Special thanks to Ali for capturing this rare “proof of life” photo of me enjoying a Turkish Rosé on the Turkish “French Riveria”.

Back during our first visit to Seliiye in 2022 we had our first flat white coffee since leaving Australia. While don’t remember if it was actually very good but if the last visit is anything to go by it probably tasted like dirty dish water strained through one of Ian’s grubby socks.

Trendy Datça

We didn’t stay long and after sourcing fuel and our dreaded blue card stamp from a neighbouring marina we sailed across the Bay of Doris to Datça, Türkiye. I love Datça, and while some might say I threw a mini tantrum when I thought we weren’t going to make it back there, I would prefer to say I was forthright during our planning session. While in Datça, a Meltemi blew in, so we ended up staying for well over a week with only an overnight trip out to Knidos to break up the visit.

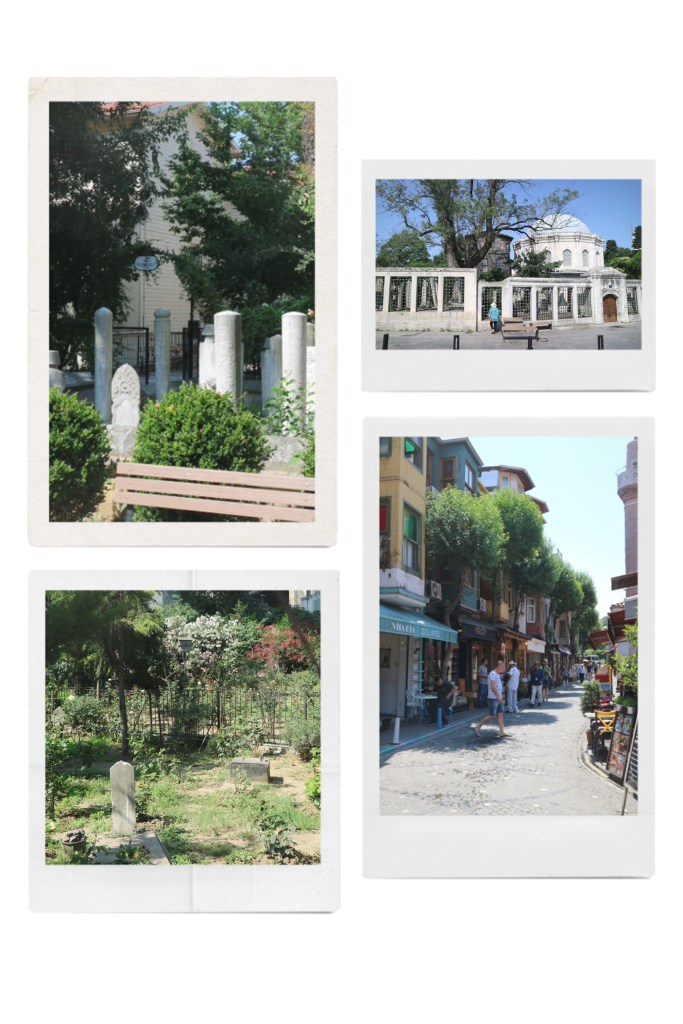

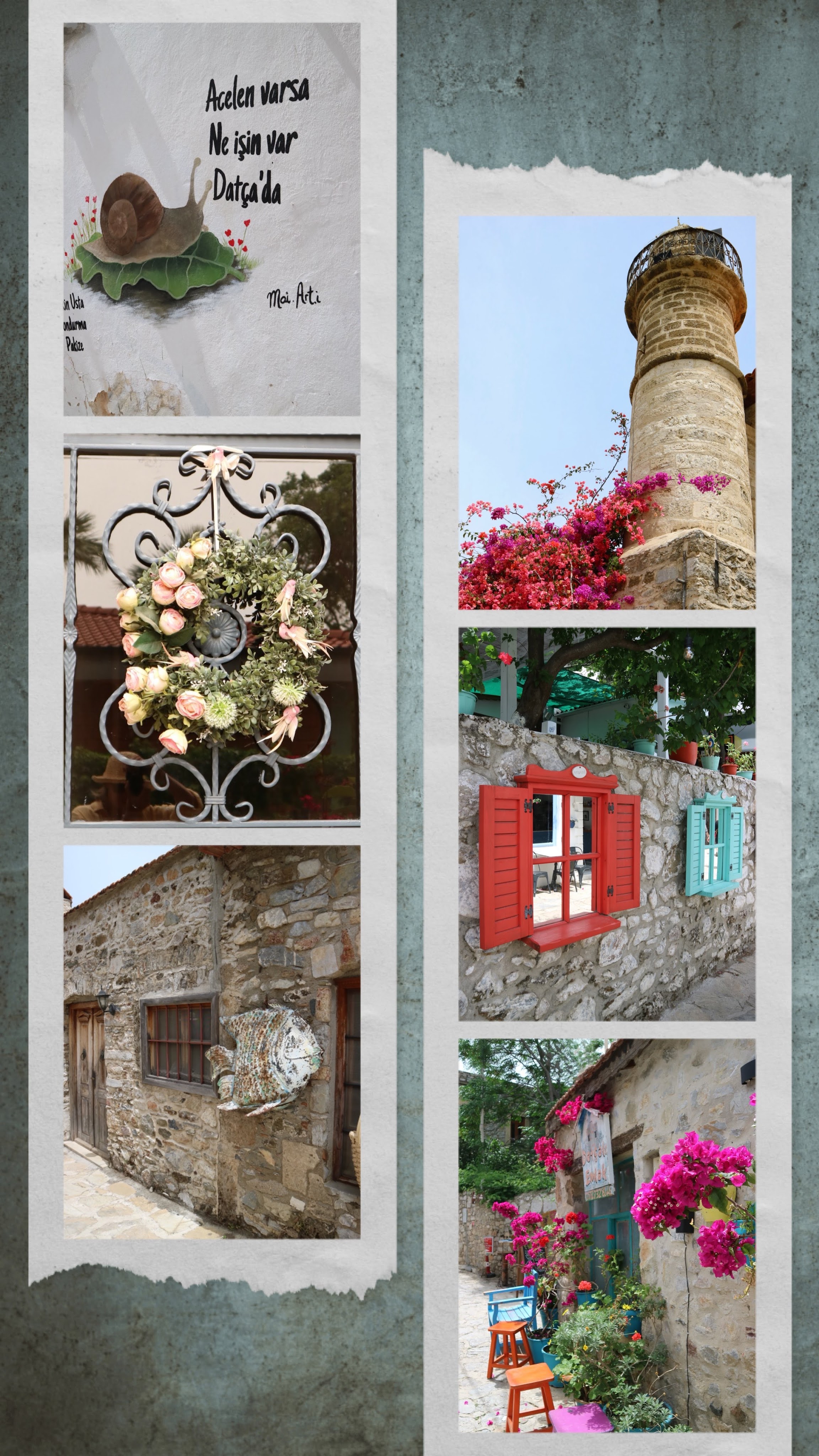

I at least was not heartbroken as we found time to check out Datça old town. It’s about an hour’s walk uphill in the heat. In other words, far enough to make us all hot and sticky and in need of an ice cream when we got there. Despite the heat it was a lovely day and there were plenty of folk out and about in the town.

The street art says “If you are in a hurry what are you doing in Datça.”

We had anchored next to the little port of Datça and near to there is a natural hot spring flows into the sea. At least it’s supposed to be a hot spring. While we were there it felt more like a tepid bath perhaps in Winter the vibe is different. These springs are open to the public (no fee) and it’s clear the locals use the amenities a fair bit. There’s a little stream between the spring and the bay where you can experience the indulgence of having your feet “cleaned” by schools of fish. While we restricted ourselves to just a pedicure some of the locals walked or floated along in the stream. I guess the last item of their to do list before leaving is to shake out their shorts. The fish aren’t small, like the ones you see in the shops that offer this back home. There were one or two that rivalled my size ten stompers. I guess they get fed well; Ian certainly provided a feast.

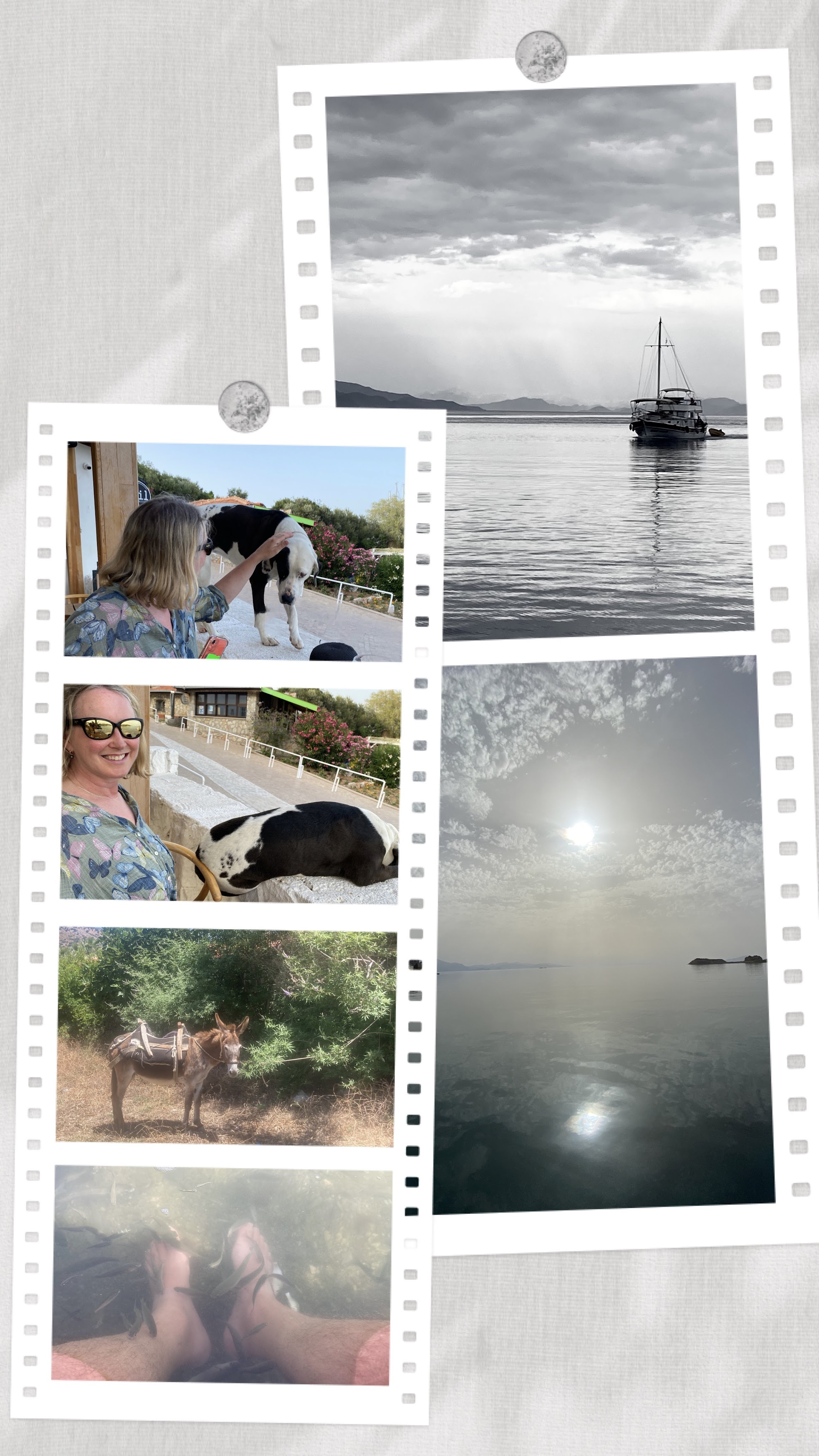

The donkey belongs to a goat herder we saw wondering along the shore of one of our anchorages.

The fish pedi is not for the ticklish.

Despite there being blustery winds much of the time we were in Datça, we had some moments of surreal calm especially in the early mornings and late evenings.

Knidos, Cnidos, Kindos, or whatever you want to call it

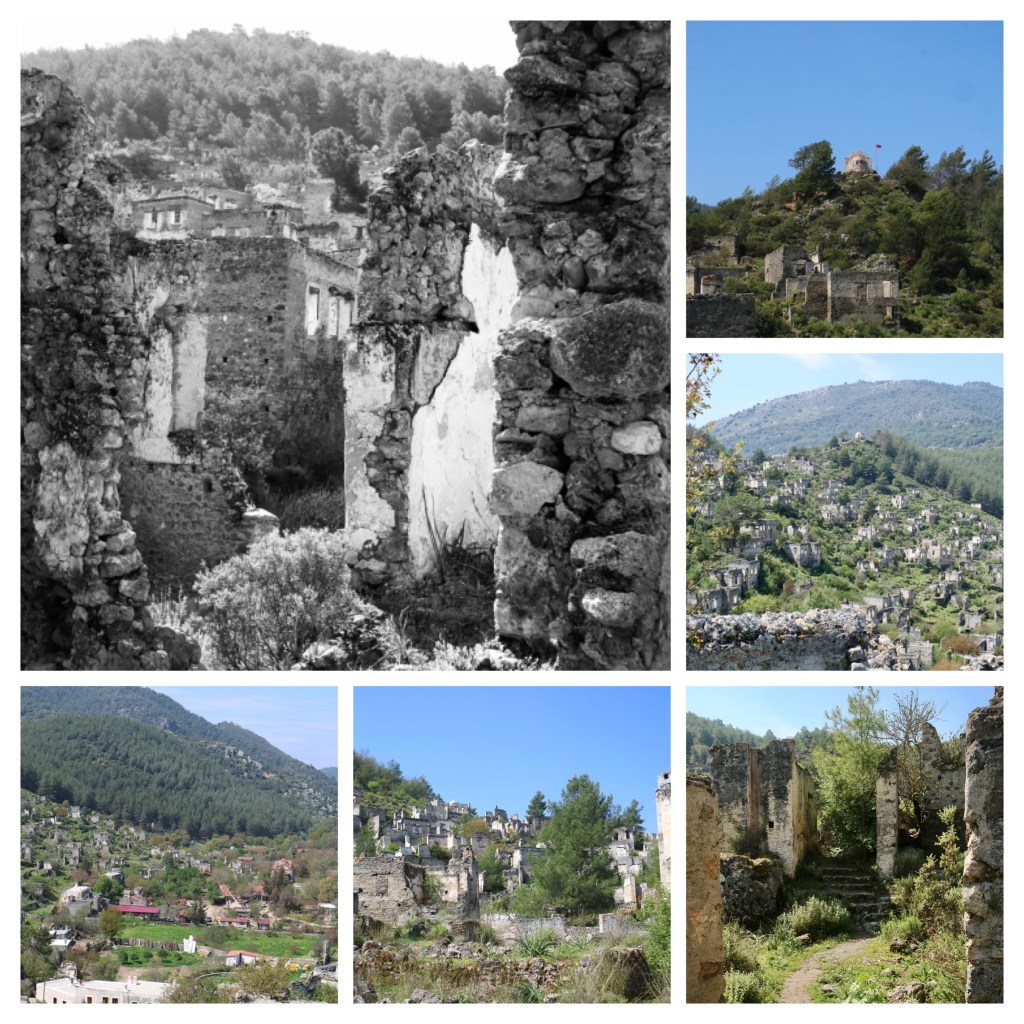

The Ruins

As I mentioned we took a day off from Datça and sailed down to the ancient city of Knidos /Cnidos/Kindos or whatever you want to call it. This must have been an impressive sea town once, with its two bays; one dedicated to the military and the other a commercial harbour. It’s mentioned in a number of historical texts as having strategic importance throughout Greek history, including the Decelean or Ionian war in which lasted almost a lifetime. The Spartan’s campaigned in and around Anatolia during this time, often using Knidos as a port of convenience. The Spartan’s played the Greeks (Athenians), the other local Leagues such as the Carians, and Persians off against each other. Reneging on their promises and changing allegiances to suit their own designs. In 394 BCE a major sea battle occurred near Knidos between the Achaemenid Empire (Persian Empire) and the Spartan Fleet which was based at Knidos during the Corinthian War. The Achaemenid’s fleet defeated the Spartans. I wonder if instead of the Spartan king giving the job of leading his fleet to a favoured relvative called Peisander, had the Spartans had hired a Scottish actor to lead the fleet if they would have had a better outcome?

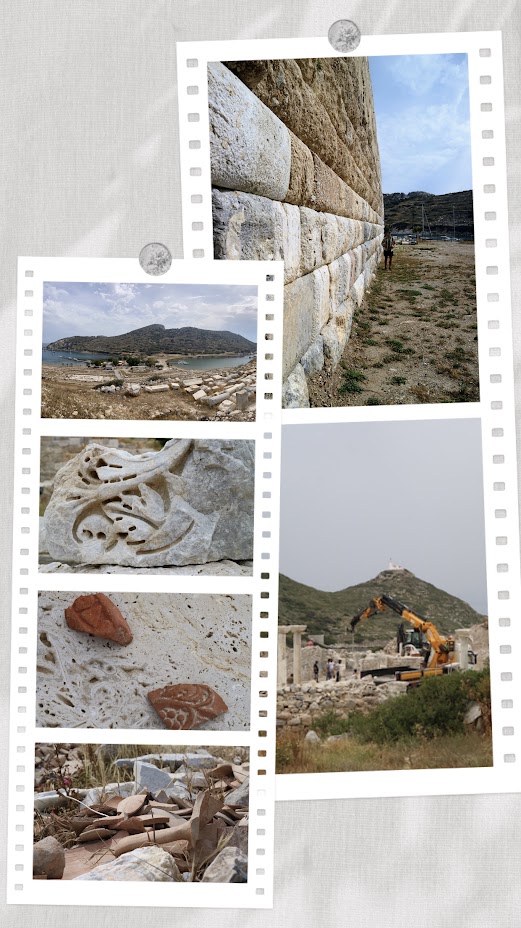

2, 3. & 4. In addition to all the temples, churches, and other buildings at many of the sites we’ve been to, there are often small artecfacts scattered about. Nowhere we’ve been has this so been as prolific as Knidos. One of the shards in the middle photo we found and returned to the front gate. The last photo is of one of the many midden heaps that can be found throughout this substantial archaelogical site.

5 & 6. Ancient vs Modern workmanship. In the top photo you can just see Ian standing next to the wall, which surrounds the Knidos theatre. The wall was built in 2 BCE by master masons and slaves. The second photo is how the modern restoration team in rebuilding the temple next door.

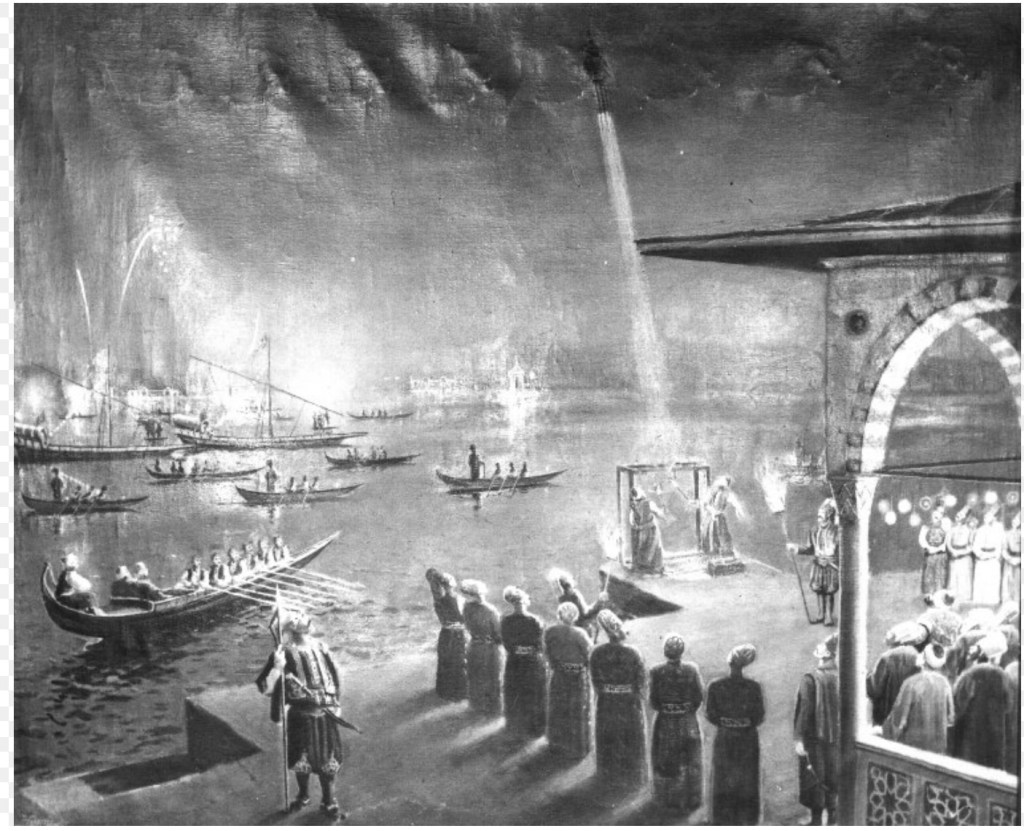

The Triremes

The mention of the military harbour had Ian and I both intrigued, so we did a little bit of googling. The boat of choice for all trend setting marauding forces was a trireme. You’ll probably recognise the picture below even if you don’t recognise the name “trireme”. They were most effective in the shallow waters of the Aegean Sea.

General Thucydides* outlined the specs for a trireme as having 170 oarsmen in three tiers along each side of the vessel—31 in the top tier, twenty-seven in the middle, and twenty-seven in the bottom. The boats were made of a thin shell of planks joined edge-to-edge and then stiffened by a keel and diagonal ribs. Each squared rigged trireme displaced only forty tons on an overall length of approximately 120 feet and a beam of eighteen feet. They were capable of reaching speeds greater than seven knots (13 km/hr) under sail. During battle the rowers were known to reach speeds as fast as nine knots **. The triremes were equipped bronze-clad rams, attached to the keel at or below the waterline; these were designed to pierce the light hulls of enemy warships. They could also be dismantled for transportation and/or destruction rendering them unusable for enemy forces.

According Thucydides tributes (or taxes) for trireme protection was calculated based on the following: 1 trireme = 200 rowers = ½ talent per month. A flotilla of ten triremes required an outlay of thirty talents for a typical 6-month sailing season. A talent was a unit of weight used to gold, silver and other precious goods. A trireme crew of 200 rowers was paid a talent for a month’s worth of work, which equated to 4.3 grams of silver per rower per day. According to wage rates from 377 BCE, a talent was the value of nine man-years of skilled work. This corresponds to 2340 work days or 11.1 grams of silver per worker per workday.

* Thucydides (circa 455 – 398 BCE), was an Athenian general who wrote a contemporary history of the wars between Athens and Sparta. **For comparison Longo weighs “just” 13 tons is fifty feet long and we average around six knots under sail however we’ve gone over nine knots on occasion. And I can confirm that our crew will never row her anywhere, anytime!”

As triremes were made of wood, they needed constant maintenance and care due to rot and damage from marine life. Tar and pitch were used as an antifouling and waterproofing coat providing protection from the harsh sea environment. Nonetheless they did not last well in open waters and were likely to succumb to extreme weather (like Meltemis). Consequently, it was regular practice to haul out the boats for extended periods even when far from home. From all of this I postulate that the triremes and their navies were the original cruisers and live aboards of the Med! I can only imagine the deck parties, BBQs, and general mayhem they would have caused to the local communities.

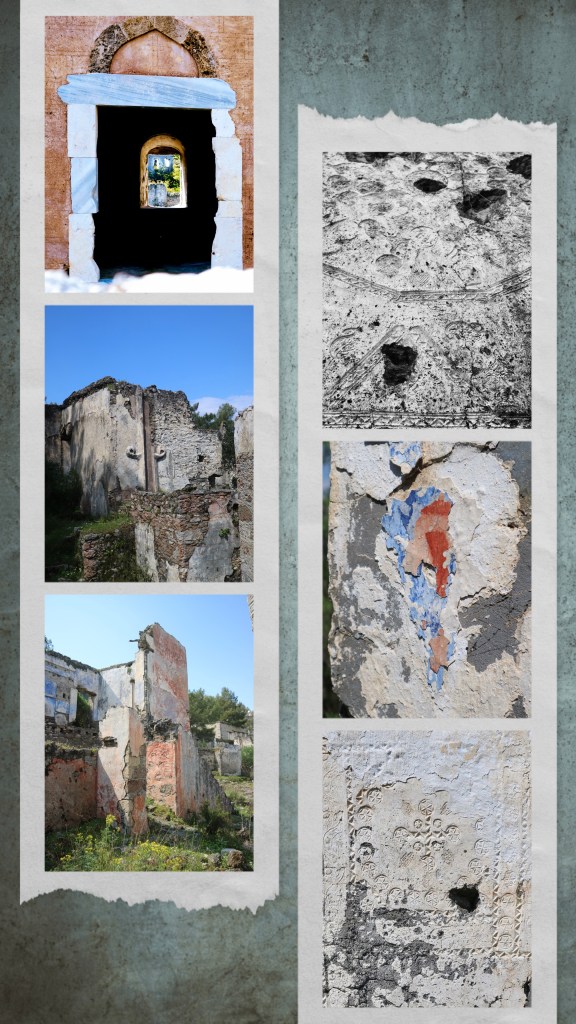

The Wonders No Longer there

Anyone who has ever been to the British Museum is likely to have seen an impressive sculpture known as the Lion of Knidos. This marble from which lion was carved comes from Mount Pendelikon near Athens and is the same kind that’s found in the Parthenon. That’s about 700 km away from its original home in Knidos. It’s hollow so it only weighs six tonnes, and measures 2.89 metres long and 1.82 metres high. There is a theory that it was part of a monument to commemorate the Battle of Cnidus, mentioned above. While it would make great reading in this post, it isn’t likely to be true as the British Museum estimates its age as somewhere between 200-250 BCE, some two hundred years after the battle. The rest of the monument which is still in Knidos has no definitive inscriptions to confirm the lion’s age or its purpose.

The lion was first “discovered” by Richard Popplewell Pullan (what a name!) in 1858 and he had it shipped to London (about 3,600 km away from Knidos) along with a life-sized marble statue of Demeter, the goddess of agriculture and of fertility dating to around 350 BCE. Demeter was the mother of Persephone, the Queen of the Underworld. An agreement made between Demeter and Hades, Persephone’s husband, to “share” Persephone. Under this agreement Persephone lives six months of the year with Demeter and six months with Hades. When Persephone is above ground with her Mum Demeter is happy: the sun shines, the crops crow and the birds and bees make merry. When Persephone is with her husband in the underworld, Demeter weeps and the world weeps with her. This story forms the basis of the Ancient Greek understanding of the seasons.

Another famous statue from Knidos depicted Aphrodite (only a Roman copy remains). Phryne of Thespiae, the model for this statue is said to have won against a charge of impiety, for participating in an orgy while partaking in ‘shrooms’. In support of her defence, she disrobed before the court. Her naked beauty so struck the judges that they acquitted her of all charges. I think Phryne incapsulates it all – beauty, brains, outrageousness, fun and self confidence. She’s my newest hero!

In 2008, Datça petitioned the British Museum for the return of both the Lion and Demeter. However, I guess the British Museum responded with a heartfelt “finders’ keepers” * since both still are in the UK. I will say though that we found a shard of pottery with a geometric pattern stamped upon it and many amphorae handle shards and pieces of painted pottery that looked like plates and bowls, strewn all over the site. Being good law-abiding visitors, we left them where we found them, except the geometric patterned piece which we placed with other pieces near the entrance.

*This is meant as humour and not a statement about who should have possession of these valuable historical artefacts. That’s a conversation I would prefer to have with an English gin and tonic in one hand and a Turkish raki in the other.

Farewell Türkiye in more ways than one

We returned to Datça to sit out a bit of a blow (aka another Meltemi) watching the local turtles and stand-up paddle boarders (SUPS) battle with the frothy swell and challenging winds. On a serious note, two girls around 11 or 12 were playing near the shore which was sheltered from the twenty-five knot winds. Once they ventured a little too far out the wind caught them, and they couldn’t make headway back toward the shore. Their stricken fathers were running along a nearby headland, but they couldn’t keep pace. Thankfully, they passed near Ray’s boat, and he heard the girls screams while he was below decks. He popped his head up in time to see them disappearing out to sea. Thankfully, a quick launch of the rescue dinghy returned the girls to their family on the beach. Ray was a little unhappy that they were blissfully ignorant to the fact it was only by chance that these two girls didn’t lose their lives.

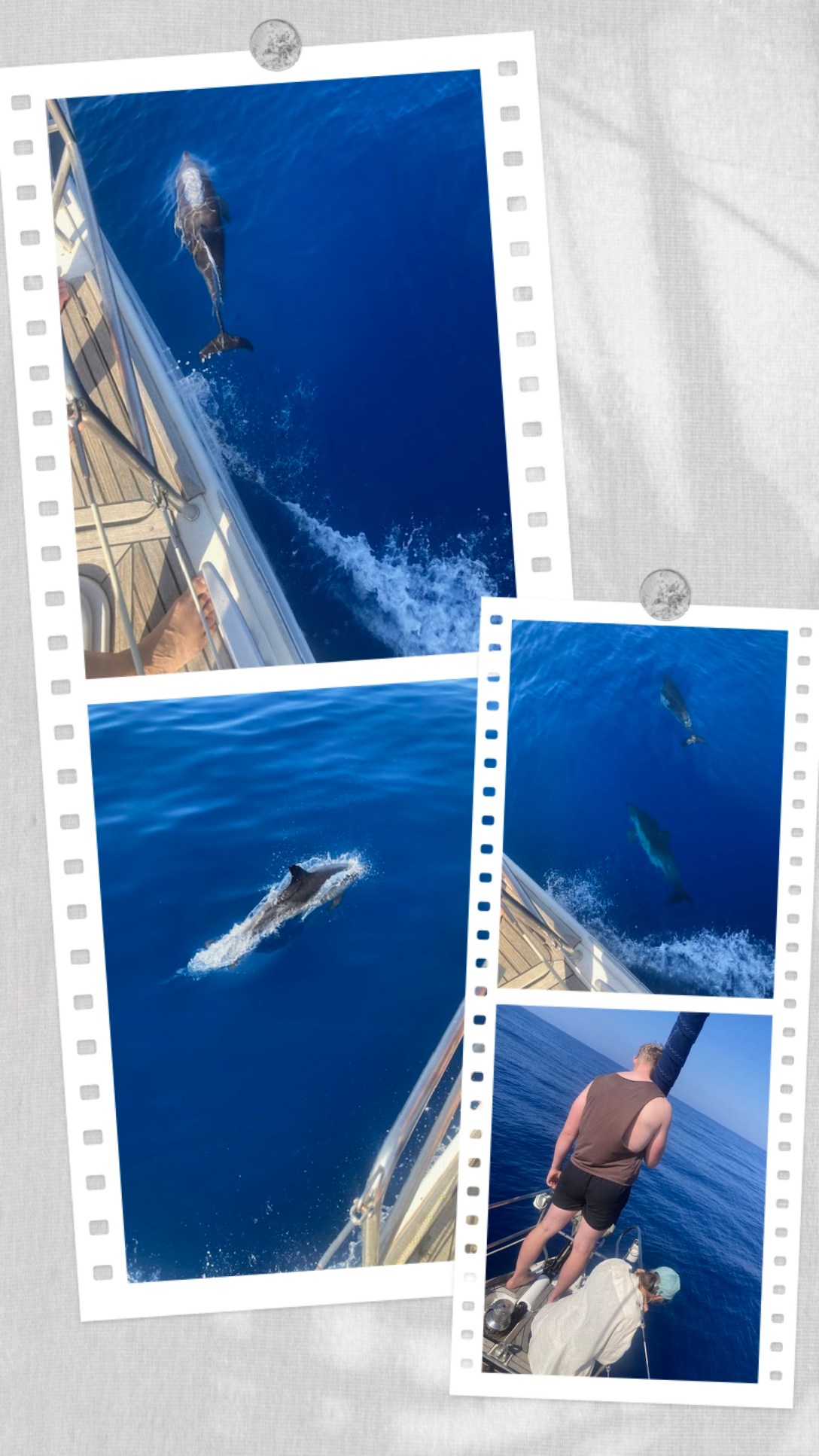

Finally, the wind abated and our time at Datça, indeed Türkiye, came to an end and on a warm summer’s day. We paid a nice man to walk our papers through the Turkish bureaucratic processes before slipping our lines and sailing the 13 nm (24 km) across the Big Blue Wobbly to Symi, in Greece. This trip took us about two hours and was completely uneventful, except for me scrambling to change our Turkish flag for the Greek flag as the Hellenic Coast Guard went by. I was going to write about Symi, our first Greek port, in this post as well, but I suspect you’ve finished your coffee and are keen to be doing more interesting stuff. So, I will say fair winds and a dearth of sea monsters until we next meet. However, for those who might recognise the name of the island – Symi, yes this is the island where Dr Mosely sadly decided to take the long way home.